This interview was published in the Summer 2014 issue of the Pulteney Street Survey, the official magazine of Hobart and William Smith Colleges. The Summer ’14 issue was devoted to the community, including pieces on the town of Geneva where the college resides.

“Down on Main Street: An Interview with Kirin J. Makker”

by Andrew Wickenden HWS’09

During a yearlong fellowship at the Winterthur Museum and Library in Delaware, made possible by the National Endowment for the Humanities, Assistant Professor of Art and Architecture Kirin J. Makker is conducting research for her book project, The Myths of Main Street, which “analyzes how the current trope of Main Street USA (local, self-sufficient, close-knit, middle-class, homogenous) is challenged by a historical reality of networked, nationally-connected, diverse place.” The book is planned for publication in 2018.

An expert in the planning, history and evolution of small towns and rural areas, Makker is examining the developmental history of small town America during its building boom (1870-1930). The archives at Winterthur are providing much of the material she needs for several chapters of the book. She documents the progress of her research on a blog, mythsofmainstreet.wordpress.com, where she writes: “‘Main Street,’ whether in a town or city, symbolizes small business and everyday hard-working citizens. In a small town context, Main Street gains mythic ideals: it is non-corporate; it is imagined to be completely separate from urban society and its ills; it is believed to be solely guided by local people and ideas. Politicians and urban planners have attempted to recreate the small town American Main Street in revitalization building and suburbia. But professional planners are distracted by the myths of Main Street, dangerously basing policy and design decisions on nostalgia and artifice.”

Makker’s other book project, Village Improvement in America 1800-1930, is under contract with the Library of American Landscape History and is due out in early 2016. Makker also writes for the popular press, her most recent piece appeared in Dwell. Published in March 2014, the article profiles Amy and Brandon Phillips, owners of Miles & May Furniture Works headquartered at the Cracker Factory in Geneva, N.Y.

Q: Where did this idea of a nostalgic “Main Street” come from?

A: There are many answers to that question, so numerous that it’s impossible to identify just one source of nostalgic Main Street. In American and British planning, small towns have been a subject of study since the profession began in the late nineteenth century. People were fearful of dense industrial cities and larger villages, with their apparent self-sufficiency and easy access to the countryside fostered many theories about ideal places to live modeled on cities around 20-30,000 people. Ebenezer Howard’s 1902 concept of “garden cities” is probably the most well known example.

In popular culture, small towns have been narrative currency since their boom period in the 1880s; it’s often the case that ‘ideal’ versions of American concepts run parallel to the development of their inspiration. But to get back to your question, one way of looking at the source of nostalgic Main Street is to look at our recent history of small town preservation and the transformation of rural village economies from manufacturing and necessities-of-life small business to a set of shops purely about leisure and lifestyle. The source of this in the last quarter of a century is in the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s launch of their Main Street Program, started in 1977. The program was started specifically to educate and help direct local rejuvenation campaigns in communities of 5,000 to 38,000 people. The program’s pilot towns were remarkably successful – Galesburg, Ill., for example, saw a 95% increase in downtown occupancy.

By the early 1980s, the National Main Street Center had grown into a robust economic revival model for small town America based in coordinated public-private partnerships, adaptive re-use, incremental growth, and clever promotional programs. The whole program was about developing a “tourist” economy using historic building stock, renovating it into a coordinated set of leisure-based businesses. Since 1980, there have been hundreds of towns across the U.S. that have successfully worked with the National Main Street Center and the program is responsible for fostering more than $55 billion in reinvestment. In addition, their approach and economic model has been used by thousands of other towns, even if these places don’t join the Center. It’s become THE approach to reviving small town America.

This is all wonderful, but there are things we should be wary of. Their formula- looking backward to an ideal Main Street- also traffics in nostalgia. There’s a little too much “remember when…” going on in the marketing materials of many small towns eager for a tourist market. This can backfire in terms of using this type of marketing to draw new residents. The whole look of the nostalgic Main Street is generally about giving visitors a way to step back in time and out of reality. I’m not certain that this strategy is the best for giving a town a vibrant future, where a diverse cross-section of people might want to make their lives. If you want to draw young people to a town, is “antiquing” it the only strategy worth pursuing? Is a Main Street of ‘leisure’ and ‘lifestyle’ ultimately going to foster a rich community life? Sure, it works and it’s better than a dead downtown, but can’t we do better and evolve this model? That’s my concern.

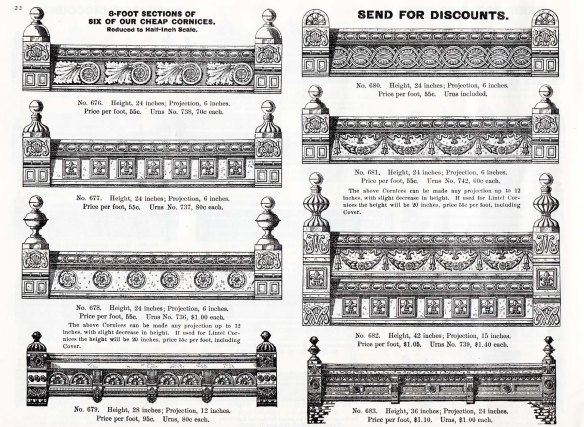

There is also a romance we associate with the architecture of Main Street that’s not accurate to its history of development. We tend to view it as a relic of simpler past, when people made things by hand, there wasn’t fierce competition or a need to get the cheapest good, and everything in one’s midst was made locally. The truth is that the beauty and quick growth of Main Street, its frenzy of economic and physical development, occurred because people were clever and took advantage of the latest technologies and markets. There was nothing quaint and simple about life on Main Street in 1900. One might even have called it “cutting edge”-they didn’t want to stay small, they wanted to be big and prosperous, however and in whatever method they could.

Q: What happened to small towns in the bust (the Great Depression) that followed the small town boom?

A: As cities struggled, so did small towns. But the truth is, small towns had always been struggling as a type of urban economy because they were not large, and thus their economy was typically less diverse than that in a dense city. When a market shifts, there are always remains of the previous boom, relics of a former time. Small towns are, and have always been, in a process of overcoming the position of being remains, just as cities have, but at a much slower rate of redevelopment. In a way, one of the reasons that the small town is a site of nostalgia is because it has been affected by busts and then has been very slow to recuperate, if it does at all in one person’s lifetime.

Q: What about today-what’s the outlook for small towns? What causes today’s Main Streets to thrive?

A: Twenty years ago, if a resident wanted to gather some neighbors together to sponsor a public art project, they had to go to the public library and do hours of research in periodicals or newspapers to find information on how to run a competition, select an artist, develop a PR campaign, fund-raise, work with the city to implement, etc. Now, you just do an hour of searching on the Internet and you’re suddenly connected with all the resources you need to mount the project successfully. Five years ago, you would not have seen a small downtown shop raise more than $8,000 in a six-week fundraising campaign in order to set up space on their second floor for drinking coffee and browsing through retail. But this year, that’s exactly what occurred in Geneva [at Stomping Grounds].

Whereas suburbia used to be the ideal among the young workforce, it’s clearly not the one and only American dream out there these days. Many young workers are choosing to live in urban settings. Small towns are not densely urban, of course, but they are sometimes preferred to surburbia by these folks.

Geneva has been on the upswing because it has an enlarging and active group of residents, a critical mass of people really invested in making the downtown into a livable neighborhood. But it’s not just that social networking has gathered interested parties in small towns together around the issue of livability and civic engagement (which it of course has), but it’s also that the small town resident can become so much more informed about possibilities and all the know-how needed to make the changes they want to see. Honestly, the future is very bright for small town America.