Who occupies the paintings of Norman Rockwell? What characteristics are imbued in the visual stories he tells?

Who occupies the paintings of Norman Rockwell? What characteristics are imbued in the visual stories he tells?

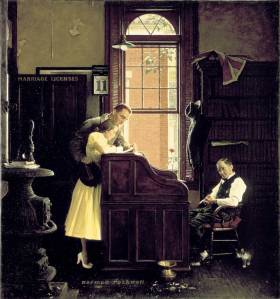

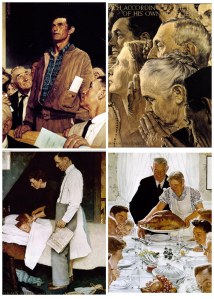

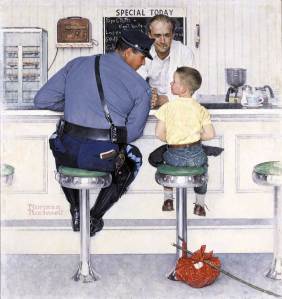

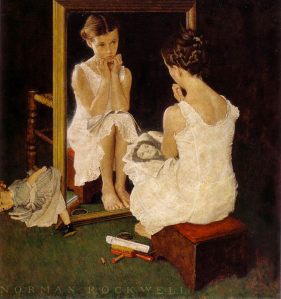

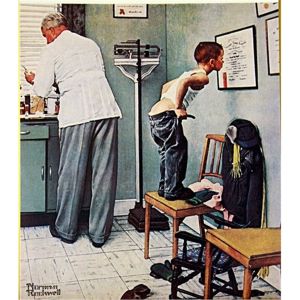

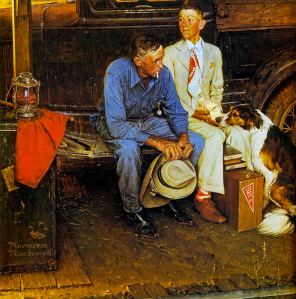

Honing in on a few of his most iconic works, we see the Rockwellian American. The Runaway, Girl at the Mirror, Before the Shot, Saying Grace, Breaking Home Ties, The Marriage License, and the blockbuster quad Four Freedoms, reveal a particular narrative about American life. Rockwell’s subjects are good citizens. Doctors take time with their patients. Policemen are just and kind. Tweens are not mean girls and their vanity is harmless. Little boys are not punks who throw rocks at windows. Adults smile and help each other out. Rockwell’s Americans are also pious. They go to church. They pray before a meal. They have family dinners. They hug each other. They enjoy a joke. They have modest aspirations. They know their place. They take care of each other. They are humble. They are honest. They are innocent. They’re not too big for their britches. They don’t abuse whatever power they have. They are moral. Their world is safe. They are honorable. They can take care of themselves. They get by happily. They don’t know suffering or poverty or the violence of crime. They don’t know the fear of racism or the humiliation of exclusion. The world is fair. The U.S. government is trustworthy. It was America in the 1940s, and 50s. He didn’t paint war-wounded GIs fresh from the war, children born out of wedlock, mad men cheating on their wives, stock brokers cheating Americans. He painted the little guy prospering on Main Street.

Honing in on a few of his most iconic works, we see the Rockwellian American. The Runaway, Girl at the Mirror, Before the Shot, Saying Grace, Breaking Home Ties, The Marriage License, and the blockbuster quad Four Freedoms, reveal a particular narrative about American life. Rockwell’s subjects are good citizens. Doctors take time with their patients. Policemen are just and kind. Tweens are not mean girls and their vanity is harmless. Little boys are not punks who throw rocks at windows. Adults smile and help each other out. Rockwell’s Americans are also pious. They go to church. They pray before a meal. They have family dinners. They hug each other. They enjoy a joke. They have modest aspirations. They know their place. They take care of each other. They are humble. They are honest. They are innocent. They’re not too big for their britches. They don’t abuse whatever power they have. They are moral. Their world is safe. They are honorable. They can take care of themselves. They get by happily. They don’t know suffering or poverty or the violence of crime. They don’t know the fear of racism or the humiliation of exclusion. The world is fair. The U.S. government is trustworthy. It was America in the 1940s, and 50s. He didn’t paint war-wounded GIs fresh from the war, children born out of wedlock, mad men cheating on their wives, stock brokers cheating Americans. He painted the little guy prospering on Main Street.

Rockwellian Americans are not in big cities, on country estates, or in Levittown. They live in small cities and towns. They live amidst a simple democratic society on Main Street where, as President Obama recently put it, “everyone gets a fair share and a fair shot” at the American Dream. Commericial places are small and double as social spaces. Public places are intimate and communally-shared. Civic space is everywhere. Barbershops are where a men’s choral group practices. It’s perfectly okay to pray in a crowded café. The train station is where you say goodbye. The  soda counter is where you are taken care of and looked after. The doctor’s office offers a glimpse of the tokens of higher education. A bedroom mirror shows you who you want to be rather than who you really are. The town office is where a marriage begins (rather than where one pays taxes).

soda counter is where you are taken care of and looked after. The doctor’s office offers a glimpse of the tokens of higher education. A bedroom mirror shows you who you want to be rather than who you really are. The town office is where a marriage begins (rather than where one pays taxes).

These images and values may be considered outdated by many in post-9/11 world, in a time of global warming, the digital visualization revolution, and the entertainment imagery of such dark humor classics as Breaking Bad and Orange is the New Black. Yet, the visual rhetoric of Rockwell’s Main Street did not disappear with the end of the twentieth century. When the towers fell, the New York Times ran full-page advertisements for the newspaper using a series of five Norman Rockwell paintings. As scholar Francis Faschina put it, these adverts were “signifiers of revisionist cultural values, selective sentiment, familiar security, and particular visions of the nation-state.”[i] After the 2008 economic crash, President Obama reassured the country that he would work to improve life for the middle class American, for those on “Main Street, not Wall Street.”

Norman Rockwell’s version of American life thus remains resonant. It is a visual rhetoric that locates the ideal locale for American prosperity in the small town on Main Street. Prosperity, too, is strictly defined by Rockwell. Success is: kindness, honesty, piety, shared community, family, humility, freedom of speech, freedom from fear, freedom from want, freedom of spiritual expression. It is not greed. It is not abuse of power. It is the very opposite of monumental. Rockwell may have employed a “realist” painting-style, but he did not convey it in the scenes he carefully staged and depicted in delicate detail. Rockwell’s America was during its own time, and will always be, mythical.

It is widely understood that Rockwellian America is integral to the Main Street rhetoric. He was and remains Main Street’s predominant propagandist. Scholars have explored the phenomenon of re-use and deployment of Rockwellian America during times of national crisis. It is widely understood that “Main Street” is powerful rhetoric, used by those marketing products and ideas to a broad cross-section of the American public, whether business leaders, politicians, activists or urban planners. Yet, Main Street’s “place-based visual rhetoric” as a device in popular culture—from advertising to political rhetoric—is largely understudied. How does a value system become one with a specific cultural landscape, the small town? How does an idealized vision of Main Street become a delivery vessel for hoped-for behavior in Americans? The power of Rockwellian American goes far beyond the boundaries of paint and canvas. The place of Rockwell’s vision of American life—Main Street and the small town—have become part of a material culture and design rhetoric, meant to conjure behavior, values, community life. It may be nostalgic, but it is employed as if it is timeless.

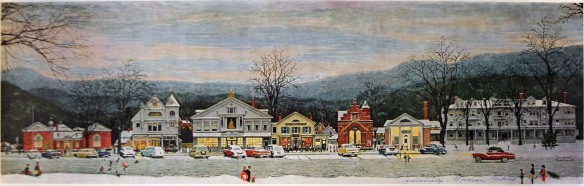

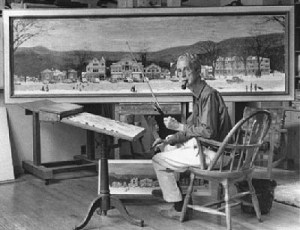

I’ve been working steadily on an essay about Rockwellian America by focusing in on the one painting he did of a town (rather than a painting in a town). This unique painting is Stockbridge Main Street at Christmas. It was the widescreen version of Rockwellian America. It’s panoramic-style revealed what lay beyond the edges of his more intimate narrative works. It was the whole street, not just one porch or street corner. It was the whole community, not just a couple of people. As mentioned, this in the only cohesive image of Main Street he published (over 4000+ illustrations!). In contrast to the bulk of his oevre, Stockbridge Main Street at Christmas features buildings, elm trees, and street lights as his characters, rather than people with animated facial expressions. This painting was the widescreen version of Rockwellian America. It’s panoramic-style revealed what lay beyond the edges of his other and more intimate narrative works. It was the whole street, not just one porch or street corner. As a rendition of the town where all his 300+ Saturday Evening Post covers took place, this painting pointed to one town as the setting of Rockwellian America. Suddenly, Stockbridge, Massachusetts, where the painter lived for the last twenty-five years of his life, was revealed to America as Rockwell’s inspirational source.

But the painting is unusual for Rockwell, the storyteller of American life in small towns. Rockwell typically staged his paintings with the people front and center. He produced rich and emotive narrative illustrations with a combination of sensitively rendered, sharpened, and finely detailed people accompanied by a selection of carefully staged props. “He was obsessed with faces and the human figure, and it would never have occurred to him, even as he sat in his studio surrounded by the majestic Berkshires, to paint a scene of mountains,” writes art historian Deborah Solomon.[ii]Rockwell was extraordinarily skilled at arranging a mise en scene with popular appeal (something not lost on one of his biggest fans, Steven Spielberg).[iii] Yet, people are not the subject of his painting of Stockbridge. Instead, buildings receive the most attentive detail.

Stockbridge Main Street at Christmas depicts a lively congenial and clean pedestrian marketplace of friendly strangers on a tiny commercial row. The architecture is highly crafted but modest. There is a decided absence of society’s social ills. The buildings, bright snow, and figure of a woman dragging a Christmas tree suggest New England. Picturesque elms, grandly lining the sidewalk patiently waiting for spring, suggest overall streetscape tidiness. The mid-century vehicles, already ten years old when the painting was finally published in 1967, lend an air of nostalgia, as does the warm glowing light from the shop windows. Beyond the buildings is an untarnished natural setting of hills with established and healthy forests. With this painting, Rockwell assured his audience that small town life was thriving where he lived.

However, Rockwell did more than paint buildings. He painted his town. The buildings are personally significant and, in a way, offer viewers a type of self-portrait. His first Stockbridge studio appears in the scene, precisely in the center of the painting. Instead of his figure in the window, however, we see a Christmas tree overlooking Main Street. His spot above Main Street assumed the position of the season’s “main” attraction. To the far left is the Old Corner House, the site of the first Norman Rockwell Museum. And at the far right, the viewer can just make out Rockwell’s home and second studio. Main Street is Rockwell. Christmas is Rockwell. Rockwell and the American small town are timelessly linked. [KJM]

Many thanks to Rosemary Krill at Winterthur Museum and Gardens for attentive editing on earlier drafts and helping me think through this work on Rockwell.

______________________________________

[i] Francis Frascina, “The New York Times, Norman Rockwell and the New Patriotism,” Journa of Visual Culture 2:99 (2003). DOI 10.1177/147041290300200108

[ii] Deborah Solomon, “America, Illustrated,” New York Tims, July 1, 2010. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/07/04/arts/design/04rockwell.html?_r=0 (accessed January 15, 2013).

[iii] For an excellent discussion of Rockwell’s skill at scene arrangement with people and objects, see David Kamp, “Norman Rockwell’s American Dream,” Vanity Fair (November 2009).

Karal Ann Marling has written a book about Christmas imagery. Part of her study includes a look at Stockbridge Main Street at Christmas.