“Made in America” is getting a lot of online traffic these days. I, for one, love perusing what’s on the Made Collection’s site to see all the gorgeous wonderful things that are handcrafted in the great U.S. of A. And as a designer, I get a personal thrill from seeing how different American companies are engaged in aesthetics, how good design has become “cool.” (hallelulia!!!)

This preoccupation with the “hand-made” is something linked to nostalgia and general romance for pre-modern times. In the case of Made Collection, there’s an obvious effort to show us how the goods for sale are not only made here, but made with care and attention—not unlike the old days when standards were higher and the process of production slower. One infers from surfing around Made Collection’s site that everything featured was not only made in the States but also not mass-produced in factories. This stuff was made by hand.

I think a similar assumption exists about the buildings of Main Street when its imagery is thrown around. At least, I always assumed that small town structures were made locally, by carpenters and craftsmen living in the town where the building went up. What do I mean? Well, basically, when I saw this:

I imagined this sort of scene just ’round the corner:

But actually, these storefronts were made in places like this:

“Huh?” (You say).

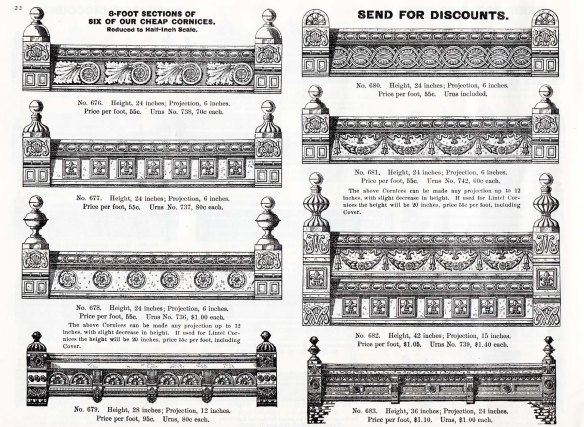

Really! You may be as surprised as I was to learn that many of the storefronts of common parlance, the visual imagery of Main Street USA, are metal (rather than hand-planed wood or carved stone). And not only that. They were most likely ordered out of catalogs or magazine advertisements from factories, produced as components, loaded on trains or flatboats, and shipped to various small town sites. Only then did local folk get involved in building Main Street, and it was more of an assembly process at that. Check these out:

The Mesker Brothers and their brother George Mesker (yes, it’s confusing—there were two companies), together sold tens of thousands of storefront components to small town folks putting up buildings. In 1898, if you had $126.70 and lived anywhere along a rail line, you could put up the front below on the left:

(That’s roughly $3500 in 2013 dollars.)

When towns were booming during the 1890s and into the first two decades of the twentieth century, settlers needed to build quickly and cheaply. Metal storefronts cost around 1/3 of what a stone building cost. Townspeople also often had to build in remote locations, places that might be far from quarries, skilled stone carvers, brickyards, etc. Although wood was used in building, it was risky: one didn’t want one’s building to go up in smoke from a negligent tenant.

There was a whole niche market, in fact, of building materials for this population. (If you are interested in learning more about the development of pressed-tin ceilings, for example, I highly recommend taking a look at Patricia Simpson’s book Cheap, Quick and Easy: Imitative Architectural Materials. It’s a great read.) The $126.70 storefront pictured above is from and 1898 Mesker Brothers catalog.

Darius Bryjka maintains a very smart and fun blog about Mesker fronts that you can find here. Partly because of Darius and partly because the Meskers were so successful selling their fronts to the small town builder, the Meskers have gained prominence in the history of nineteenth century metal storefronts (Okay, maybe Darius isn’t responsible for the prominence of Meskers in the history of vernacular architecture, but — and he of course humbly protests this claim — but his blog is still really really great and he was the original force behind the ongoing project “Got Mesker?“).

But even beyond the Meskers, there were hundreds of other companies and foundries offering metal building components. And it’s this regional distribution that I personally find fascinating. While the Meskers sold nationally, there were other companies that manufactured storefront components as side jobs for regional markets. For example, Union Iron Works in San Francisco, which mostly produced steam engines, got its first big revenue stream through the selling of architectural iron castings made from fire-ruined safes, hinges, stoves and sheet iron bought on the cheap. Salvaged iron purchased for ¾ of cent per pound was refabricated into a host of building ornaments for structures going up in outlying areas, turning a tidy profit at 20 cents per pound. Not too long ago, I found some storefront components by Union Iron Works on some buildings in downtown Petaluma, CA.

That a storefront in Petaluma, CA was assembled with building components from San Francisco, and made from recycled steel to boot, demonstrates how complex the production of Main Street really was. It’s a reality check, to be sure. These Union Iron Works storefronts in Petaluma were not made by Mr. Jones, local carpenter, with wood chopped down from his neighbor’s woodlot and hand-made with skills passed down from his grandfather. Okay, it’s not romance, but hey! It’s just as beautiful and wondrous a story! There were people thinking outside the box here! Being industrious and clever! Making America with innovative business practices and new technologies!

One of the myths of Main Street is that it was Local. I think because small town America is steeped in ideals, it’s difficult to be precise about what “local” meant. In today’s Main Street/Wall Street dialog, local suggests small business operations, local industry and labor.

I had always assumed that the storefronts of small town America were built with mostly local materials and labor; i.e. they were hand-crafted. Taking a peak into the archives of metal storefront trade literature, however, shows us a different tale that helps dispel the myth of local Main Street. A storefront going up in Petaluma helped an innovative business practice occur in San Francisco. Petaluma fueled a city’s economy, a regional economy, and played a role in the U.S.’s import of iron ore. Main Street was local in many ways, but it was made through its relationship to national and global markets as well.[KJM]